Wanderful Loves

Working together as Studio Job, artists and designers Job Smeets and Nynke Tynagel have built up a distinctive, wide-ranging and internationally acclaimed practice that consciously draws on the traditions of the past to create a visual culture absolutely expressive of its own time. In projects ranging from a mass-produced postage-stamp to weighty and monumental works of sculpture, from architectural friezes for social housing developments to intricate marquetry cabinets, they have created an expressive revival of the decorative arts for the twenty first century.

Following studies at Design Academy Eindhoven during the 1990s, Smeets (1970, Hamont-Achel, Belgium) and Tynagel (1977, Bergeijk, the Netherlands) established Studio Job as a joint enterprise in 1999. Deploying bold graphic patterns and cartoonish vernacular forms, as well as the elaborate decorative sensibilities and dark mood of the North European Gothic, their work was, from their earliest collections onwards, utterly unlike anything else on the international scene. Within a few years, their attention-grabbing creations had become a regular feature of exhibitions in museums and specialist galleries, and had started to find their place in important international collections.

METADESIGN

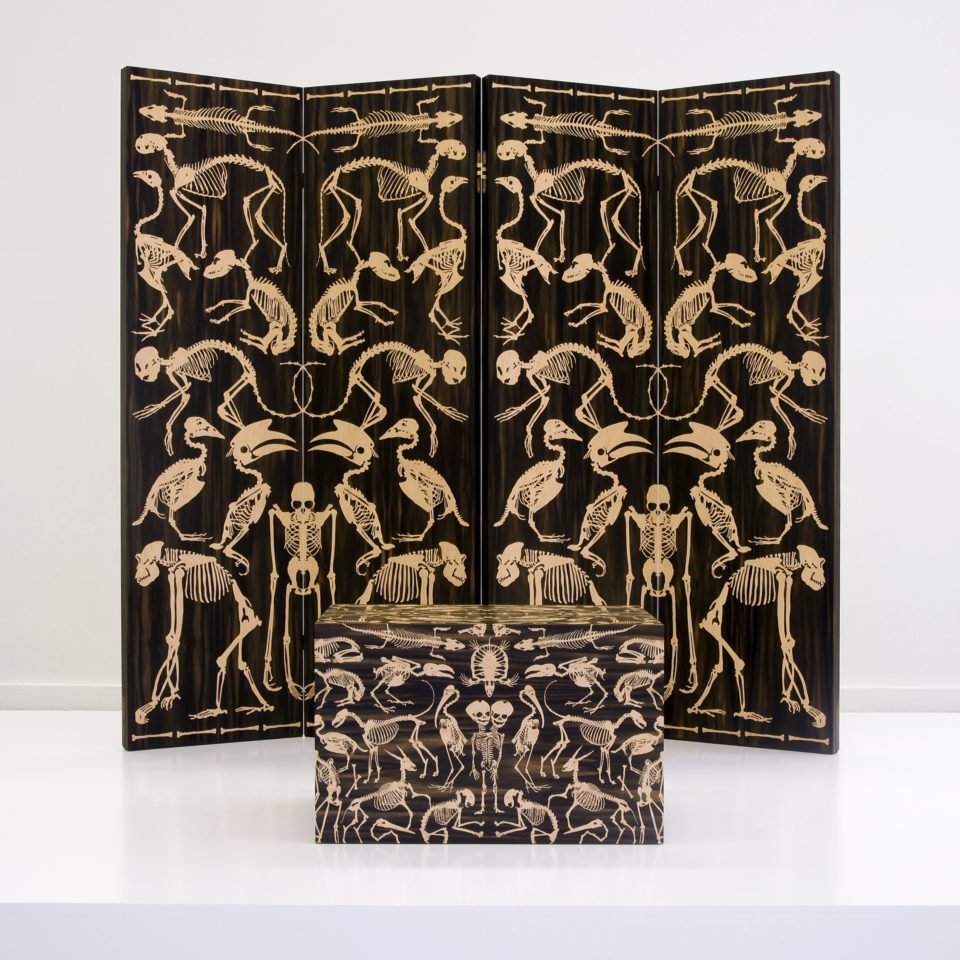

Key among the early support for the Studio was an exhibition at Hasselt’s Z33 House for Contemporary Art in 2007 – No. 16 STUDIO JOB – the first extensive monographic show dedicated to their work. The exhibition included cabinets from the Perished (2006) series, inlaid with a pattern of zoological skeletons in Macassar Ebony and Bird’s Eye Maple; outsized ‘domestic objects’ in bronze, glass and wood from Home Work – Domestic Totems and Tableaux (2006-2007); a patinated bronze castle and bust from Oxidised (2003); and jagged blackened and polished bronze seating from Rock Furniture (2003-2004).

By the time of the exhibition, Studio Job had already worked with celebrated design firms including Bisazza, Koninklijke Tichelaar Makkum and Swarovski, but while they exhibited at design fairs and exhibitions, and were represented by design galleries, their work did not (and does not) fit comfortably into a utilitarian discipline. Instead, one might see their oeuvre as artwork that uses the vernacular language of design. Or perhaps as meta-design – objects that appear to be functional, but the actual ‘function’ of which is to provoke questions surrounding use, making, collecting and the acquisition and display of wealth and taste.

Taste, and its related snobberies, are prime Studio Job territory. The trappings of class and social position are regularly inverted or subverted. In the Home Work series, domestic objects including pots and pans, a coal scuttle and a mug tree are rendered in outsized, polished, bronze. These objects are not only mundane, but represent a superannuated nostalgic vision of a simple, unpretentious working homestead. In the Gold Biscuit (2006-2007) series, gilded crockery stands in for the ‘best’ china of a bourgeois home, the tasteful pattern motifs of the original here replaced with symbols of the counterculture of another age: CND insignia and peace signs.

ICONOGRAPHY

The Robber Baron (2007) collection includes a bronze wardrobe with ‘shot through’ doors and a glistering surface relief compiled from iconography relating to weaponry, toxicity and pestilence. A table top is formed from polluting clouds pouring from factory chimneys and a safe is opened by twisting a clown’s nose: wealth, of the kind required to purchase pieces such as these, is traced back to roots in violence, dirt and exploitation.

Already, in these earlier collections, Studio Job drew on the skills of expert artisans to explore and expand the language of traditions such as marquetry and bronze casting for a contemporary context. In the following years, the studio repertoire expanded to include works in stained glass, hand-painted Delftware, and cast iron. Their work steadily established itself as an ongoing reproach to the anti-embellished minimalist forms that functioned as shorthand for good taste, and which seeped further and further into the mainstream in the decades that followed Modernism. Studio Job relished kitsch; the clash of ancient tradition and modern iconography; painstaking handiwork and cartoonish graphic shorthand: they represented the laughing triumph of form over function.

The Z33 exhibition featured many works already purchased for the collection of the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands. Other significant monographic shows at major institutions followed, including the Groninger Museum itself in 2011, and, more recently, the 2016 exhibition Studio Job MAD HOUSE at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design. Their work is represented in leading collections worldwide, including the Cooper Hewitt and MoMA museums in New York; Rijksmuseum and Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Victoria & Albert Museum, London; Al-Sabah Collection, Kuwait; and the Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein.

While their studio practice has expanded over the years to include commercial (if highly unconventional) product designs for brands such as Moooi and Seletti, Studio Job’s core concern remains an exploration of the teetering edge between use and ornament, excess – be that of ideas, materials, references or all of the above – and clean, precise, composition.

Hettie Judah: We often look into an artist’s early life and the atmosphere and geography in which they were raised, and try to identify the origin of particular preoccupations and themes in their later work. If we were to do this with you as a designer, what elements from your own background would you identify that have fed through into your later work with Studio Job?

Job Smeets: To answer your question with a thought: aren’t there always also other reasons? I totally believe in influences from our youth: not only for artists, but for everyone. But in adolescence, university and later, crucial influences – a breakup, for example – play an important part.

The length of the ‘early life’ depends from person to person. Personally – and I don’t think I am an old soul – it might be that my early life continues until the end. Within the work it’s different though. It’s more visual. Containers (2000), our first bronze works are lovely, naïve and raw, but our work changes through the influence of time. In work you become increasingly expert, but life stays abstract.

HJ: The design world is very international: you sell your work in London, New York and Miami and have collectors all over the world. Do you think that there is still a ‘sense of origin’ in your work as a designer from Benelux?

JS: The more you travel, the more you become universal or international. You gain icons, archetypes and memories. Yes, we’re from Europe. Benelux is too small a categorisation – it’s just a political or commercial border. When it all goes well, you leave the nest and try to fly on your own. To develop a voice of your own.

HJ: Do you think a sense of origin is tangible in your work though?

JS: ‘Le Plat Pays’ – as Jacques Br el puts it. Literally a thick fundament of humus, clay, soil, bricks and turf in the Low Countries. All nicely compressed and solid: hardened by time.

HJ: We’ve spoken in the past about your interest in particular museum collections in Europe – could you tell me about the aesthetic and decorative arts traditions that inspire you and on which you draw in your work?

JS: Well I must admit, looking at our work, it becomes more and more universal, and less connected to a specific area. It took four years for us to study Modernism, ten years to study the ornament and more than fifteen years to study Europe. We work a lot in the US right now, which is also inspiring! Donut!

HJ: What role have museums played in your own career? Is support from non-commercial institutions important?

JS: Museums are very important. They give you the chance to focus solely on the work and the installation. The story… Collectors collect the bricks and the museum builds. Although these days, private collections more and more take over the public collection. Is that a pity? Maybe… maybe not. But without the collector there is no museum… I’m equally happy with both: institution & private sector. Both feed each other.

HJ: While art and modern design are popular exhibition subjects in museums, decorative arts seem not to be – at the Wallace Collection in London for example, visitors tend to look at the paintings but not the beautiful pieces of furniture or porcelain. Do you think people no longer know how to ‘read’ these works? Do you think that we’re so used to mass-produced goods that we have lost our appreciation for them?

JS: Is that true? I always look at everything to be honest. Don’t underestimate the viewer! But if true: decorative arts need better PR and maybe even a better name.

HJ: We last spoke quite a few years ago after perhaps the Delftware collection or a collection of marquetry cabinets – you were very inspired at the time by what seemed like a constant search for different artisans to work on each subsequent collection. I have a couple of questions in connection to this. Are you still regularly engaging with new disciplines in the applied art and crafts?

JS: Yes, sure, but only because we need them. It’s not because we want to display crafts per se.

HJ: How much does your investigation into craft techniques inform your design work – is the craft always at the service of the design or do you sometimes design to showcase a particular craft?

JS: The craft is always at the service of the design: always. The brain is the filter, not the machine. Unless the brain asks me to leave the decision to the machine of course!

HJ: It seems to me that the high production standards in your work rely to a large degree on your engagement with groups of skilled artisans – are you always able to find the skills that you need or have there been some techniques that interest you that have slipped out of the makers’ repertoire?

JS: Well, it depends on whether we’re working on an object or a product. We are very ‘Renaissance’ and occupy a broad field: sculpture, design, fashion, music, architecture and graphics. As long as the translation is perfect and the work contributes we are happy.

HJ: I regularly hear the complaint that young people are no longer interested in learning applied skills that will lead to a role in making – they all want to design, be that in fashion or products – does it worry you that you might be part of the final generation of designers that can work with highly skilled and experienced artisans in the way that you do?

JS: No, we do it all. Super unique and super industrial…a ten-meter-high sculpture in Miami and the King’s postage stamp in The Netherlands that’s produced in an edition of ten million. But also: do you really believe avant-garde design is becoming more and more industrial? I’m not sure.

HJ: When I last interviewed you about six or seven years ago, you were engaged, by and large, in very limited production – design art works that were available in very small editions. Since then you seem to have augmented your engagement with…if not mass exactly, certainly larger production. I’m thinking here of your furniture and lighting collections with Moooi, tiles with Bisazza and garden furniture for Seletti (please feel free to inform me here if there are some significant collections that I’ve overlooked!). What considerations did you have in shifting from very limited production to something wider?

JS: That seems to not be in line with your previous question but: no, we do both… but ‘industrial design’ and ‘sculptural design’!

HJ: Does larger production demand something different of you as a designer/ studio?

JS: Yes, totally. In our case, an industrial production is never produced in house.

HJ: At the time of the Delftware collection I asked whether you’d consider putting the designs into wider production and I recall your saying that you weren’t sure people really wanted to have such provocative motifs on their cereal bowls – do you think the ‘mass’ audience has become more open-minded and adventurous now?

JS: You must mean The Last Supper (2009)? We never put it in a larger production so I can’t compare. But many things are born in the avant-garde or ‘Haute Culture’ and develop into the mainstream…

HJ: A final question: are there any particular areas in design that you have not yet had the chance to explore, and that you are perhaps excited to experiment with in the future?

JS: We’ve never worked for Porsche or Apple!