Wanderful Loves

Martin Margiela radically changed the fashion system. For more than twenty years, the Belgian fashion designer has worked his magic, focusing on concept, emotion and product, while keeping himself out of the spotlights. Yet, the invisible man is still a major influence in today’s fashion arena.

“Is it really something in the water?” The question came from a guy who was queuing up, just like me, waiting to get a cab. It was London Fashion Week and some of the Belgian fashion designers had again shown how daring and different from the rest they were. Was it something in the water? What could I say? I didn’t have a set answer back then – it must have been the end of the 1980s – whereas today I would say: “Of course it was.”

Martin Margiela, and his colleagues and designers from the group they called the Antwerp Six – who all worked separately but are often talked about in one and the same phrase – all studied at the fashion department of the Antwerp Royal Academy of Arts, but Margiela’s roots are in Genk, where he grew up and went to art school as a youngster. Friends from back then remember him as an art enthusiast, who later on in life went crazy over fashion. “We never took time to eat”, remembers make-up artist Inge Grognard, who established Maison Margiela’s beauty look, working alongside Martin for all the visuals and fashion shows. She still is one of Martin’s best friends and has fond memories of the time they went to art school together. “We loved clothes so much, it became an obsession.”

Margiela moved to Italy after graduating in 1980, but soon learned that Paris was the better option, to be fully connected to the world of fashion. It took him dozens of phone calls before Jean Paul Gaultier took time for a one-on-one interview, but eventually he landed the job and stayed for almost seven years. Maison Martin Margiela was started in 1988, together with Jenny Meirens, who became Margiela’s third eye and managed the business – Jenny knew fashion inside out because she had previously run two boutiques in Brussels, selling collections which included those of Beretta, France Andrevie and Comme des Garçons.

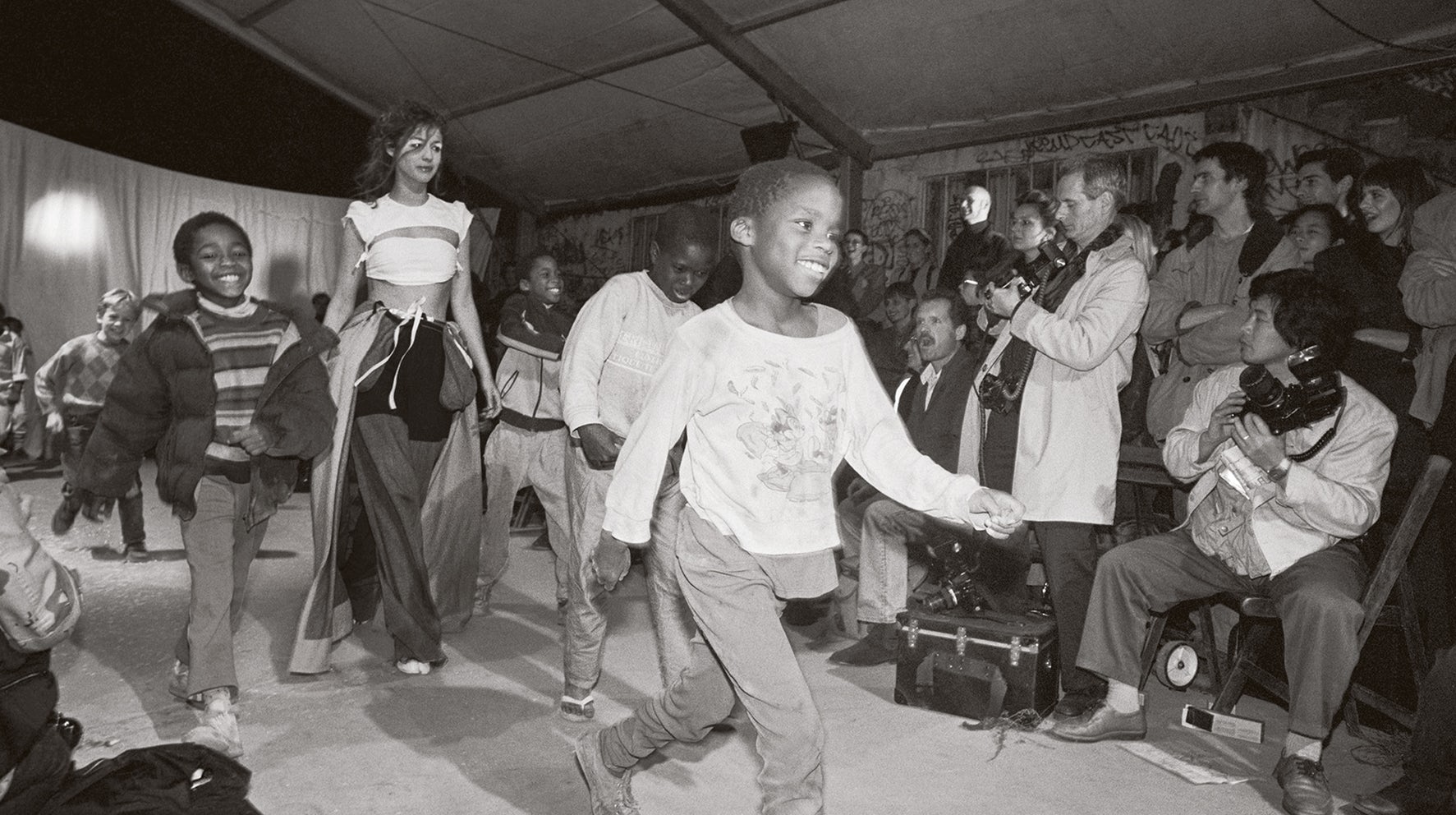

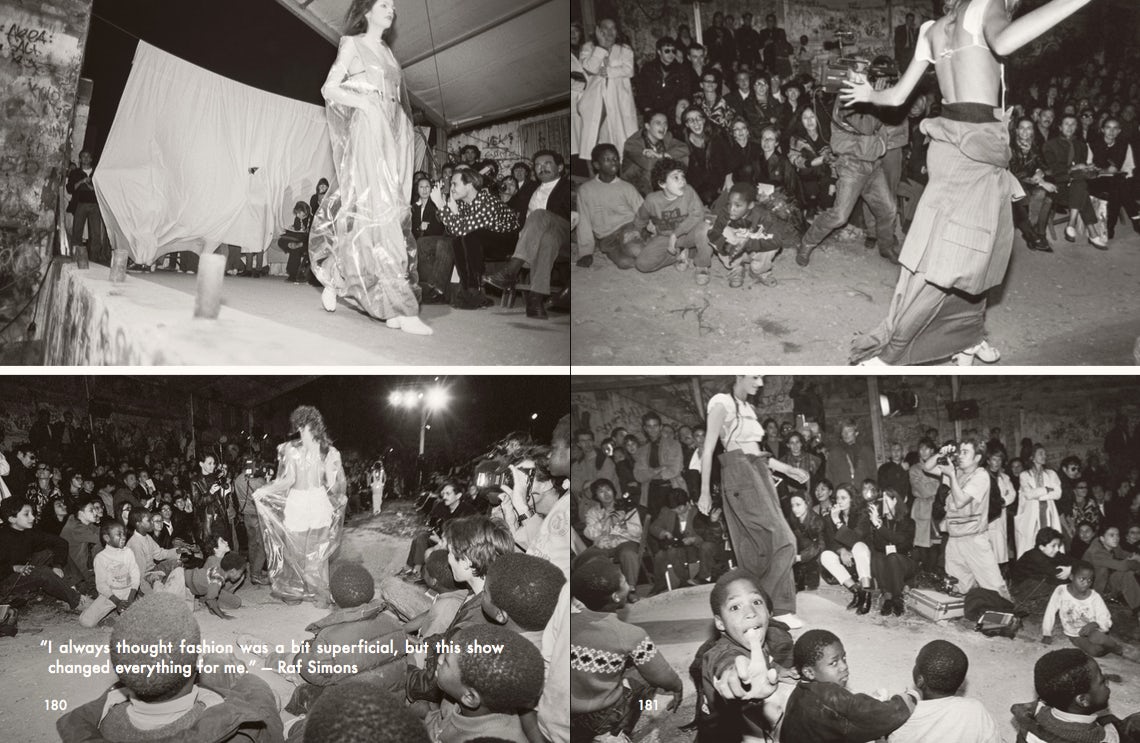

The Margiela business started with great ideas but no money whatsoever. Choosing Paris as the Maison’s headquarters was Margiela’s own idea: he wanted to show his vision to the entire fashion scene. Staying in Antwerp – which most of his fellow designers did at the time – seemed to him like a waste of time. He saw the big picture: with a studio and a great team, with a fashion show, going for the real game. Although he was keen from the start to play it by his own set of rules. The first shows were so daring and so different that some fashion watchers cried – Jean Paul Gaultier himself told the media that Margiela hardly needed help. He was good enough to build his own brand.

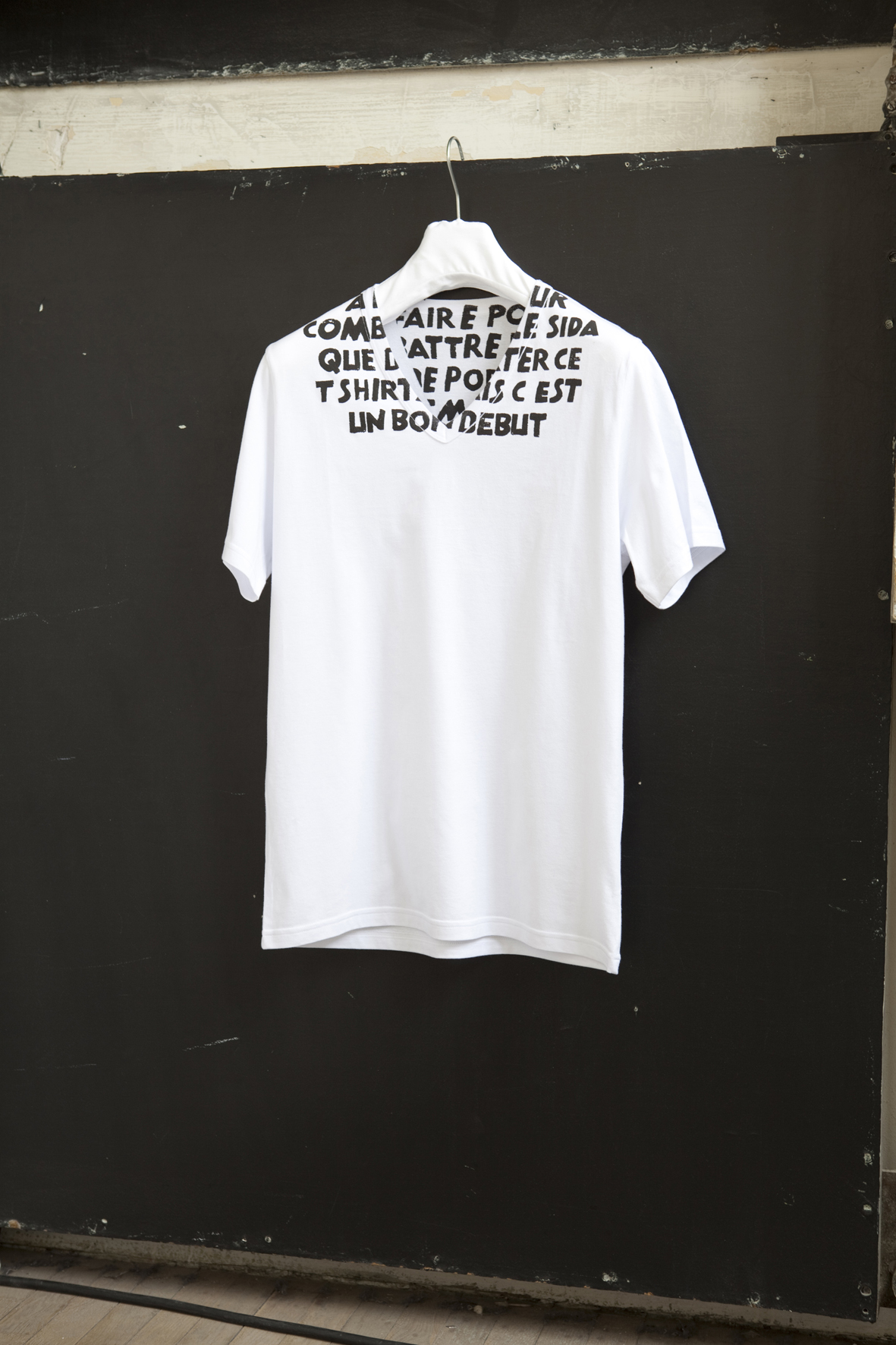

After these first seasons, Maison Martin Margiela kept going at a steady pace. With no investors at all – the first years were a financial nightmare – but with a very clear vision of what fashion should be: contemporary, inspirational, visionary, boundary-breaking, for real men and women, far away from the obvious glamour and glitter and in particular, well-made, the emphasis being on handmade techniques, real craftsmanship and savoir-faire. Margiela evolved into a master tailor – the fact that a luxury label such as Hermès took him in as creative director of the womenswear – in 1997, he stayed until 2003 – is proof of his extraordinary skills. Deconstructing and then reconstructing, making new forms based on old garments, often bought at flea markets in and around Paris, the Maison established a true DNA that had nothing in common with the rest of the fashion scene – except perhaps the Japanese designers who were equally exploring what fashion could be.

A lot has been said about the start of Belgian fashion, and how Margiela and The Six went about their business. What is very important as to how they all built their brand is that they were free. Coming from Antwerp or – in Margiela’s case – hailing from Genk, in Limburg, meant that there was hardly a fashion heritage to be protected or to be cherished. These designers could build up a world of their own. Margiela’s view on things was, of course, extra affected by his roots: the son of a coalminer, he grew up in a city where there was poverty and unemployment, and where future prospects were often harsh and dreary. Margiela fled to Paris, and I do think there was no Plan B. He had to make it. That too is very Flemish: the idea to just go for it, whatever comes your way or might hinder you. “Being a pioneer felt amazing”, said Jennie Meirens in De Morgen Magazine in 2013, “We hardly slept and worked very hard. We trusted our gut feeling. And we knew that one day, the business would be successful.”

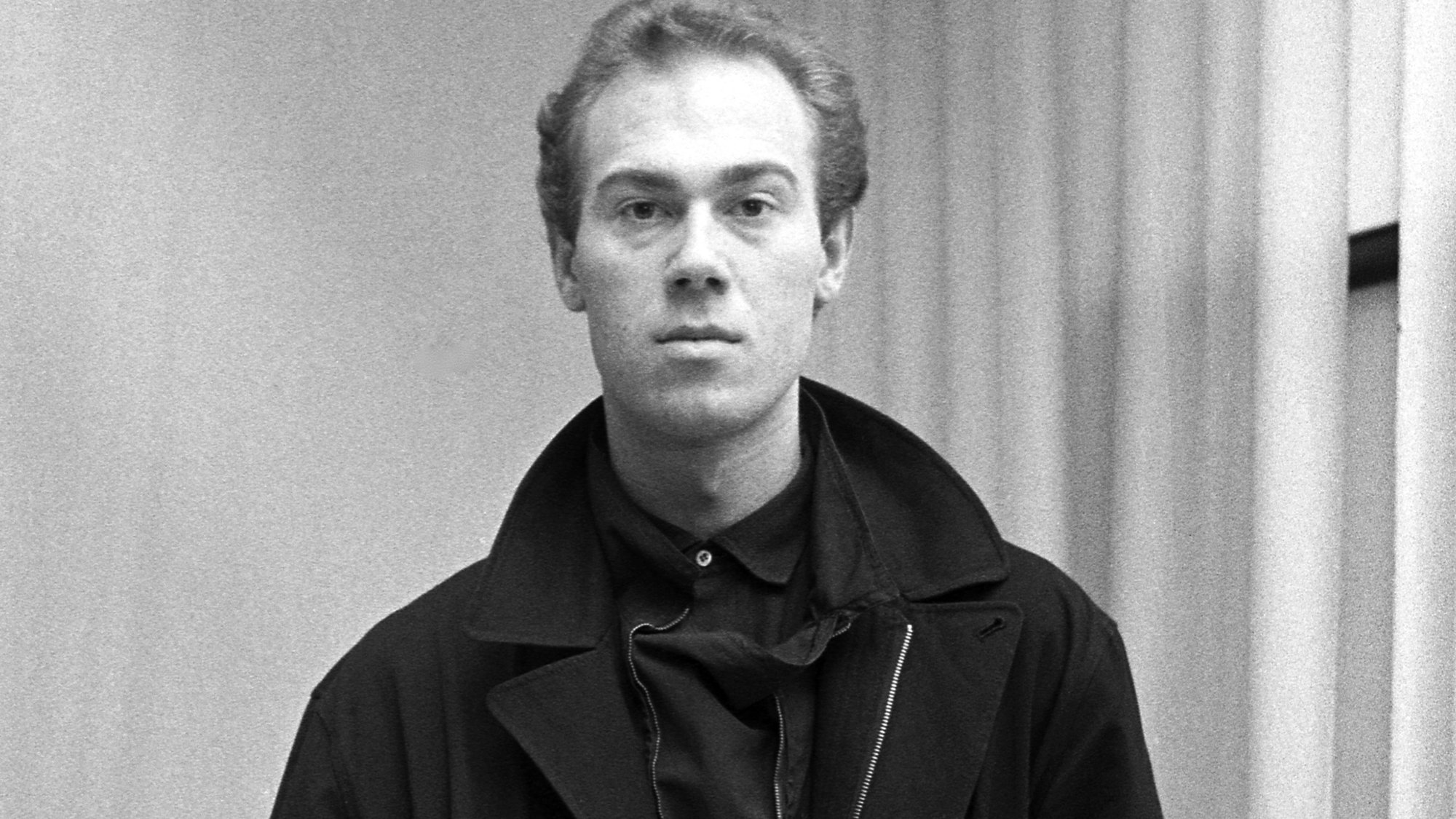

Margiela took a decisive step from the very start of his business: he didn’t want to be the centre of attention as the designer of his eponymous brand. He refused personal interviews and only talked to the press by fax (and later e-mail), always adopting the pluralis majestatis. The story was never about him, it was always about the brand and how a team was making it all work. He projected that idea onto his catwalk, often hiding the faces of his models – women from street castings, never regular models. And even the showroom, and later the stores, were predominantly all white: old furniture was repainted in white or was enveloped with white canvas. Again: the main focus was on the clothes, it was always about the project, never a personal ‘look at me’ story. That too can be regarded as a distinct Flemish feature, a typical way of keeping a low profile and not wanting to get noticed. I had the chance to talk to Martin Margiela at the beginning of his fashion career and even then, he only wanted to discuss the collection, never his personal life.

Margiela set a new standard in fashion. To most fashion editors his energetic vision on fashion – and the almost visceral way he handled glamour – was hard to understand. To some, his looks were downright grunge or punk, or whatever excuse they found not to go and see the show. It took years for some high-end fashion journalists to attend a Margiela show. That all changed when Hermès asked Martin to become their creative director for womenswear. Suddenly, Martin was part of the elite, and the Maison was in for more serious reviews. The Hermès job absolutely played a major role in the acquisition of the Maison by Renzo Rosso – which took place in 2002. Even today, the impact of the Margiela DNA is enormous. Alessandro Michele, Gucci’s creative director, has definitely learned a lot from the Margiela school, as has Raf Simons, who calls Margiela his absolute hero. An entire generation of fashion students grew up with the deconstruction theory that made Margiela a case study, even in marketing schools. And what about Vetements, the recent ‘collective’ project headed by Demna Gvasalia, the Georgian designer who studied fashion in Antwerp too, and has recently been taking the Paris fashion scene by storm? Gvasalia worked for Margiela for a couple of years and is also keen on changing the fashion system, by collaborating with other brands and even taking his collective into the realm of haute couture. Maybe Martin Margiela likes Vetements´ work, maybe not. We will never know, will we?