Wanderful Loves

“The moment the mines closed,

it was as though the cork popped out of the bottle, with a bang,

and a host of new initiatives and ideas shot out.”

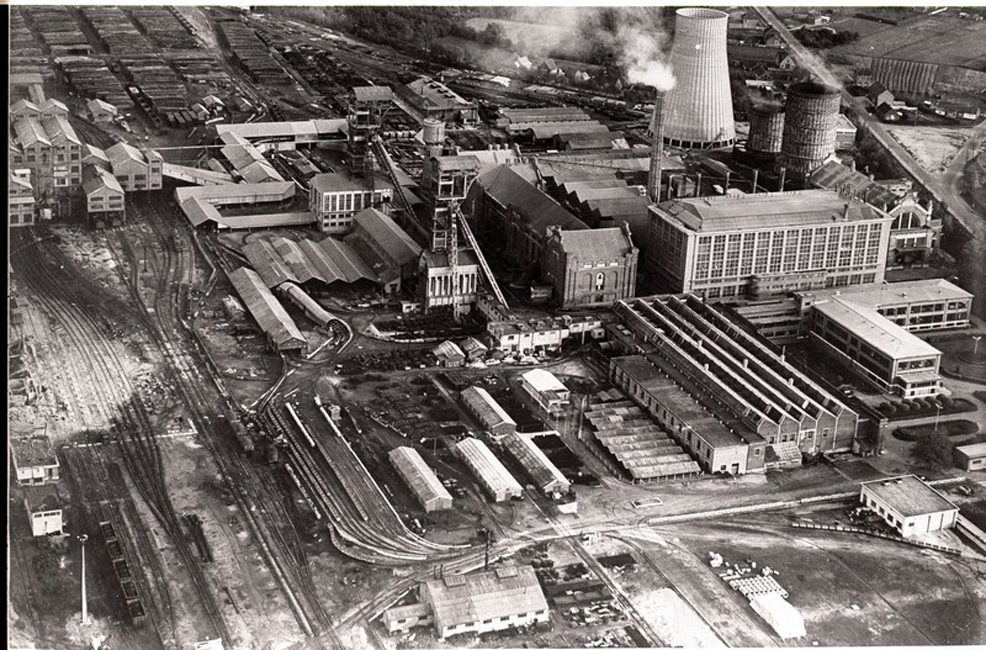

Undoubtedly, the coal mining industry brought great progress and welfare to Limburg in the first half of the 20th century. Seven coal mines transformed sparsely-populated villages on the heath into overly-large municipalities, concentrated around the shaft towers and mining installations. Decades later, the reconversion of this ‘black industry’ has contributed to creativity in the region. So writes Ivo Vanderkerckhove, editor-in-chief of Het Belang van Limburg, a national newspaper but most importantly, the number one medium in the region.

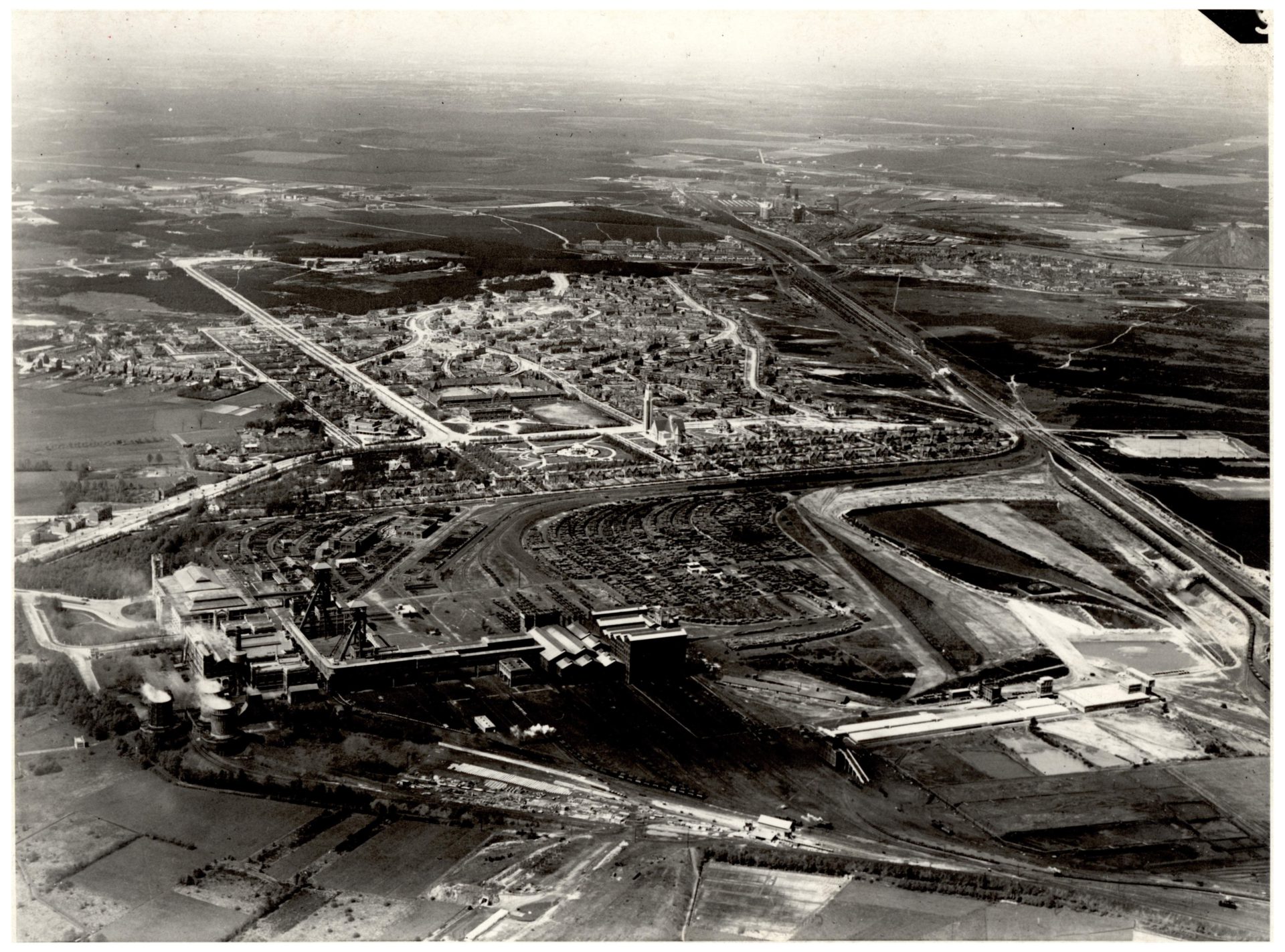

The coal mining industry provided a huge amount of jobs: there were many people needed to work in the pits at Beringen, Zolder, Houthalen, Zwartberg, Waterschei, Winterslag and Eisden. Right from the start, there was a call for immigrant workers. Belgians rejected the hard, dangerous work underground, certainly at the beginning. The first immigrant workers came mainly from France, Germany and Eastern Europe, but were later followed by Italian, Greek, Spanish and Portuguese workers. At the beginning of the 1960s, the mine owners also recruited workers in Turkey and Morocco. The arrival of all those people, first the men alone, and soon after the wives and children, caused a veritable melting pot of nationalities and cultures in the Limburgse Kempen. Genk was by far the largest mining municipality, with three mines within its boundaries. Nowadays, there are more than 150 different nationalities present in Limburg.

Developing the mining industry in Limburg ate up enormous amounts of capital, yet despite all the money flowing to the pits, the Limburg mining industry was profitable only for a few decades. Alarm bells were rung in the European mining regions as early as the 1950s. The outdated mining areas of Borinage and Luik closed down in quick succession and Limburg was not spared either. The Zwartberg Mine, the most modern of the three mines in Genk, was unexpectedly and rudely closed in 1966, and this was an economic, but even more, a social drama. There were even two deaths at the gates of the Waterschei Mine on 31 January 1966. The Belgian government went so far as to announce a state of emergency, and sent soldiers to Limburg. After the government´s promise to never again close a mine without first ensuring alternative employment, things calmed down again in Limburg, thanks also to the ´Akkoorden van Zwartberg´ agreement.

Early in the 1960s, the American automotive giant Ford was introduced in Limburg, and with the official opening on 27 October 1964, a new economic impetus was fact. When the factory started, it employed 5,000 people, and the company expanded to become the largest Ford factory in the world. In 1994, no fewer than 15,000 people worked on the Ford site, and thousands more at the many suppliers.

LEGACY

Although the growth at Ford Genk had given the region hope, the closure of the Zwartberg Mine signalled the start of a long-lasting death struggle at the 5 remaining Kempen Coal Mines (KS). The ‘Akkoorden van Zwartberg’ agreement forced the government to search actively for new employment in Limburg. From the beginning of 1986, the situation for the mine itself became untenable, because the national government shut off funding completely. The third constitutional reform redefined the Belgian public system, and the financial model in which the coal mines would fall under regional authorities. Flanders would from now on have to pay the deficits in the Kempen coal mines, and to do that, it made use of income from inheritance taxes. In 1985, the KS was suffering losses amounting to more than the entire annual sum of inheritance taxes (between five and six billion Belgian francs, roughly 180 million Euros) and the Belgian Prime Minister Wilfried Martens (CVP) sounded the alarm. A crisis manager was sought, and found, in 1986 in Thyl Gheyselinck, who had previously carried out a number of international assignments for Shell.

Ironically, the coal mining industry in Limburg was originally set up mainly to provide the Luik blast furnaces with the coal they needed, but neither the French nor the Wallonian owners had thought about a processing industry, in the immediate vicinity of the seven coal mines in Limburg. That too was a defining detail in the further development of Limburg. And yet, slowly but surely, a network of suppliers began to develop around the mines. This secondary industry focussed mainly on the processing of wood and metal, initially almost exclusively for the mines, but as things began to go badly with coal, they too started looking to diversify, and found solutions in the construction of heating elements, among other things. Well-known brands such as Vasco, Radson and Jaga owe their success to the malaise in the coal mining industry.

Crisis manager Thyl Gheyselinck had to get to work immediately, to dam the losses, and when he presented his plan on 8 December 1986, his verdict was merciless: the loss-making mines were to be divided into two parts. The eastern mining area – Eisden, Waterschei and Winterslag – would be closed immediately, and the western mining areas – Zolder and Beringen – would stay open for at least ten years. Gheyselinck received funding of 100 billion Belgian francs, spread over the whole period, of which 28 billion was intended for the closures of the mines in the east. At that point, there were still more than 18,000 people working for KS. In response to offers of special pension plans and generous severance pay, 10,000 employees chose to leave the mines, in a short space of time; more than expected.

This enabled the dismantling process to be carried out more quickly and KS needed less than the 28 billion that had been earmarked for the closure and the social assistance. Gheyselinck had agreed with the government that any money left could be used by KS for the development of new initiatives in Limburg. The quicker he closed the East, the more money would be left in the envelope with the 28 billion francs. That was the financial basis for the reconversion of the mining area. When the Flemish government decided, two years later in 1992, to close the remaining mines at Zolder and Beringen earlier than agreed, this arrangement, beneficial to Limburg, was repeated, only this time in what was known as the ´half franc´ arrangement. Now, one half of the amount spent that was less than the amount originally budgeted, would be given to KS for reconversion.

The ambition was to reduce unemployment in Limburg to the average in the rest of Flanders within ten years. To achieve that, not only money was needed, but also new businesses and initiatives. Gheyselinck took the money he had saved and set up the Limburgse Investeringsmaatschappij (LIM) or Limburg Investment Society, which provided risk capital to entrepreneurs in the mining area who planned to start a business: a monetary catalyst. At the same time, he developed his own project, with KS: ERC (Educational, Recreational and Cultural) project. The idea was to erect a huge ‘experience park’ on the mine grounds in Waterschei, where the three elements of ERC would have a place. The plans were megalomaniac: film studios, golf courses, a shopping centre, a covered football stadium, a cultural centre and so on. It was to be the beating heart of renewal in central Limburg, and in the long term, it would provide more employment than the original mining industry had. In order to realise all this, and create employment at the same time, Gheyselinck set up his own construction company for the unemployed miners. This manoeuvre went together with countless political appointments to boards of commissioners and made crisis manager Thyl Gheyselinck the most powerful man in Limburg. He also gained credits: not only had he helped the Belgian government to get rid of a huge coal problem, he had done it more quickly, and with less money, than originally expected. And he set up new initiatives which gave hope to the region again. That was made more so by the man’s ambition to go down in history not only as the man who had closed the mines, but as the man who had saved Limburg.

His plan was to wipe clean the slate of the mining past. All mine buildings were to be demolished. And with the motto ‘From Black to Green’, a reallocation plan was developed for the various mine sites, supported in part by the regional authorities. Only a limited number of buildings and installations were left standing according to that script. This led to huge protests by groups who, on the contrary, were concerned about preserving the past with its industrial archaeology and the heritage department made its voice heard. When Gheyselinck subsequently wanted to grab the Winterslag site too, a Limburg Minister, Johan Sauers, blocked the plan. He put pretty much everything still standing at the various mine sites under temporary protection orders. Between 1993 and 1995, he converted the status of 45 buildings from temporary to permanent protection, as Kempen mine monuments. Thanks in part to this, the buildings of the former coal mines above ground form the most important concentration of industrial archaeology in Flanders.

In 1992, Zolder closed down; the last mine. But Gheyselinck had been gone more than a year by then. He resigned in May 1991, when it became clear that the Flemish government of that time no longer supported him. The permits necessary for his most important project, ERC, were never issued, despite the fact that he had managed to convince his private investor (the British Stadium group). The ERC project, once described as megalomaniac, was reduced to a mainly tourist shopping project with the new name, Fenix (phoenix). The private investor whose interest Gheyselinck had already attracted, was just as happy with the new plan. However, Gheyselinck’s successor, Peter Kluft, was equally unable to get the slimmed-down project up and running, partly because of resistance from the traders’ association NCMV (later known as UNIZO) which felt the project was a threat to the existing Limburg traders. On 20 January 1998, the SECD (socio-economic committee for distribution) issued a negative recommendation, for the second time, and this time, Fenix was no longer able to rise from the ashes.

In the aftermath of the closure of the last coal mine in September 1992 (Zolder), an undignified fight took place in the wings at KS, and parliamentary pressure was brought to bear to ensure that the court investigated the financial wheeling and dealing at KS. The scandals forced the Vlaamse Raad to decide, in 1994, that the reconversion of Limburg required more transparency and structures that were simple to inspect. A series of non-profit organisations and SIM (social investment society) were abolished, and the Limburgse Reconversiemaatschappij (LRM) was set up, under the direct supervision of the Vlaamse Gewest regional authority.

Stijn Bijnens (born 1968) was appointed to run the LRM. Bijnens had been nominated ‘Manager of the Year’ in 1999, while he was the founder of Netvision (later Ubizen) and with his appointment, a new era of modern management dawned. The capital which LRM now has to work with, originally came from the money Gheyselinck saved at that time. A quarter of the entire 100 billion Belgian francs, made available at the time by the government to solve the issue of the coal mines, was never spent. KS was allowed to keep half of that 25 billion to invest in the new initiatives. That remainder has now become a real rolling fund. “By buying and selling, and dividends, we’ve spent that start capital at least 7 times over”, says Stijn Bijnens.

Stimulated by Bijnens, the structure of LRM was simplified even more: whereas previously LRM took decisions about both the purely economic dossiers, and advised on strategic and non-profit related investments, that ‘social component’ was shut down in 2008. “Managers and economists should decide on economic dossiers, and social dossiers are for the politicians”, according to Stijn Bijnens. “We pay dividends to the Flemish government almost annually, and they transfer that money to LSM (Limburg Sterk Merk), a fund with which elected politicians (regional authority) can decide what should be done with it.” Since 2008, LRM has already paid 236 million Euros in dividends to LSM, by way of the Vlaams Gewest, and this social reconversion model has become a great example for other countries.

BE-MINE Beringen

In Beringen, the entire heritage site was protected, including the cooling towers. Today, this is the largest mine site in Europe (it covers an area of 100,000 m² of existing property portfolio), fully intact and with a fantastic reallocation. At Be-mine, as the project is called, there is room for shops, a museum about the history of the mine, a swimming pool, the unique TODI diving centre, an adventure mountain and an indoor climbing centre. The be-MINE housing area is situated on the mine’s former wood park. This used to be where the wood which was used to shore up the mine tunnels was stacked. The residential care facility and the first apartments are ready and have been delivered. They form the first component of the development of the housing area, which will comprise more than 500 accommodation units, to be developed over a period of ten years.

GREENVILLE Houthalen

Greenville NV is located in the former head office of the Kempische Steenkoolmijnen in Houthalen, and is the new clean-tech incubator, the ultimate location for businesses from the green economy. Greenville NV offers companies a wide range of services. The location has at its disposal 3,500 m² of office space, 500 m² of rooms for meetings and seminars and a clean-tech visitors centre. Companies which settle here can make use of a central secretariat and the company restaurant.

DE SCHACHT MINE SITE Zolder

The Zolder mine started in 1923, and was the last mine in the Benelux to close down, in 1992. A few important buildings in the former mining settlement were given monument status in 1993.Most of these have already been reallocated, such as the beautifully restored power station. The former bathhouse now contains a cafeteria, and houses the Centrum voor Duurzaam Bouwen (CEDUBO). The administrative head office has retained its original function, only now it’s shared by a number of businesses. The winding engine room is now called ‘De Verdieping’, and is a multifunctional building housing a passive school, among other things, and the ZLDR Luchtfabriek, a huge space in which you can experience the mining past in all its glory, opened on 24 April 2015.

THOR PARK Waterschei

Thor Park is a global development project for the reallocation of the former Waterschei mine site to a hotspot for technology, energy and innovation. Thor Park is growing rapidly into a technology park, 93 ha in size, with international appeal and activities, where the city of Genk and the partners make interesting links between research and development, innovation, industry, development of talent and urbanism. Thor Park is being developed according to a high-end quality concept in the field of architecture and landscaping, taking into consideration sustainability and park management. Thor Park offers space to innovative businesses and organisations, to thinkers and doers, and profiles Genk as the smart technology city of the future. Waterschei houses Thor Park technology campus, EnergyVille research centre and Thor Central, among other things.

C-Mine Winterslag

C-Mine, located on the site of the former Winterslag coal mine in Genk, resolutely focuses on creativity. Parts of the mine buildings and installations have been preserved and given monument status. The buildings now house a cinema (Euroscoop), a number of bars and restaurants, and facilities for meetings and congresses. Piet Stockmans has a studio here too. The Media & Design Academie is represented on the site, and the Genk Cultural Centre is also here. C-Mine won the Vlaamse Monumentenprijs award in 2013. C-Mine Crib leads the way in creative innovative business, acting as an incubator and service centre for starting and young creative companies.

BIOMISTA Zwartberg

The Zwartberg mine, which closed back in 1966, will house world-famous artist Koen Vanmechelen’s arts project La Biomista, in and around the former director’s house. From 2018, heritage, modern art and biocultural diversity will come together in a unique way. La Biomista will house the studio and foundations of Koen Vanmechelen. This internationally renowned artist’s work will be exhibited in the park. Interesting to know: La Biomista means ‘mixed life’.

MAASMECHELEN VILLAGE Eisden

Maasmechelen Village was set up as an outlet shopping village in 2001. It is situated next to the mine shafts of the Eisden mines, closed down in 1987. The Limburgse Reconversiemaatschappij took part in this, to stimulate employment of low-skilled workers. As well as the brand name Maasmechelen Village, there is also a cinema complex, a high-class hotel, Ter Hills recreation park and the gateway to Connecterra, Limburg’s most beautiful hiking area.