Wanderful Loves

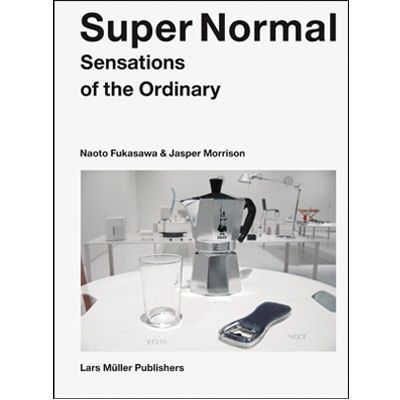

There’s something strange about design and time. Good design is timeless, and seems not to suffer from the laws of time. The fact that the beauty of timeless design demands to be understood completely, is actually a quality, and adds depth to things. In Jasper Morrison’s vision of design, beauty is “not just beauty quickly perceived but beauty on other levels, the beauty which takes time to be noticed, which may become beautiful through use, the beauty of the everyday, the beauty of the ugly and the useful, long-term beauty.”¹ A designer, however, is more strongly bound with time, whether he likes it or not. After all, time does not easily let itself be formed. One may believe that ‘in the meantime’ offers a lot of space, but ‘time is mean’ and leaves no space.”²

Furniture maker Casimir (1966), who trained as an industrial designer at SHIVKV in Genk, knows only too well how unavoidable the laws of time are. He has been producing pieces of solid oak furniture since the 1990’s, archetypes which can be ‘read’ in a variety of ways, and which seduce subtly by way of their material and clean lines. The pieces of furniture are indisputably ‘present’, but at the same time abstracted from a clear here and now, because of their remarkable shadows. Casimir consciously produces the furniture traditionally. Recent comments made as a result of his solo exhibition at Galerie Valerie Traan, confirm that he has felt the same way about the essence of his work all those years: “While beauty is a fundamental fact, not at all bound with time, trends or fashion can be described as consumer deception. […] I’m not interested in furniture which will be passé in five years time. My Schaal 1 is already 25 years old, but still relevant. I’m working on an oeuvre that has to stand the test of time. And in the end, it will be time that decides whether or not my work was worthwhile.”³

However, restrictions in production and logistics, and the disadvantages of heavy, wooden, space-consuming furniture which reacts to dampness, lead to his later deciding to launch a design label for which design products are manufactured industrially. He includes the Flemish-Burgundian character that he recognises in his work, in this label, which starts up in 2004 as Vlaemsch(). The collection receives an enthusiastic response. Unfortunately, the label turns out financially to be ‘a premature baby’, as Casimir describes it regretfully, in 2005, at the cancellation of the label presentation during the Milan design week. The industrial project is forced to shut down in 2009. But Casimir ‘rises from the ashes of Vlaemsch() with unusual designs such as the Ladder book rack, the Poutrel sofa and the Kist chest of drawers. The circle closes seamlessly.”4

Time bears him out on this. The fifteen new pieces of furniture, shown in 2015 at Galerie Valerie Traan, display again clearly what the designer-maker has known for years. His work is back in the spotlight, in a here and now which expands into what has already been, and what is still to come.

At other times, the public performance of designers creates a huge social dynamic. The presentations are public tilting moments. Everyone is familiar with the Antwerp Six, partly due to the nickname given to the fashion designers collective by the British press in 1986, at their presentation during the London British Designers Show. The international success of the Six – Walter Van Beirendonck, Ann Demeulemeester, Dirk Bikkembergs, Dries Van Noten, Dirk Van Saene and Marina Yee; later also known as 6+ because Martin Margiela had been invited to join them, but later left, only to be replaced by his former girlfriend Marina Yee – reflected on the fashion programme at the Antwerpse Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten, from which the designers all graduated in the early 1980s.

Their international breakthrough signified an important turning point for the school and made Belgian fashion an item. They greatly influenced the fashion of the 1990s, and brought about a new era. The momentum of the Six never actually seemed to come to an end, even though the designers all went their own ways after 1986, and Marina Yee even turned her back on the fashion world for a while. She disappears from the stage sometimes, only to return in a new role, with theatre costumes, a collection of interior fabrics or her own perfume, in addition to her fashion collection.

—